Was ist Mokume Gane?

Are there imitations of mokume gane rings?

If you take a closer look at the Internet and some of the stores offering mokume gane rings, you will notice that there are very different versions and qualities of this technique. The Japanese term mokume gane initially means nothing more than "wood-structured metal" and says nothing about the exact manufacturing method and quality of the ring or wedding band described as such.

As we repeatedly encounter this uncertainty in our day-to-day work when advising our customers, we would now like to provide all interested parties with a clarifying overview of the known forms of this technique. For this purpose, we have given a name to the known characteristics in order to distinguish them clearly from each other.

After all, the price of a product is always linked to its quality and the service offered, even over the years.

- Gravo Mokume

- Mokume Cover

- Mokume Seam

- Mokume Seamless

We at "Wiesner - Die Goldschmiede" do not want to presume to declare anything right or wrong. Everything has its justification if it is offered for what it is. However, it is important to us to name the different qualities.

Mokume Gane wedding rings from our workshop in seamless technique:

Gravo Mokume (engraved pattern):

Gravo mokume are rings or wedding rings made of stainless steel, as well as precious metals such as yellow gold, white gold, red gold, etc., which are engraved with a pattern. the pattern of a mokume gane wedding ring is engraved on the surface of the ring. This can be easily recognized by the fact that there is no pattern on the inside of the rings or that the pattern itself is not two-tone. It is possible that an apparent two-tone pattern may have been created by blackening the engraving using a laser or suitable chemicals.

If the engraving is sufficiently deep, it may also be possible to cover the engraving with a second color. For example, by incorporating yellow gold into the engraved pattern of a white gold ring. The production of a wedding ring in GravoMokume is relatively simple and quick. For example, with an engraving laser.

Mokume Cover (Mokume plated):

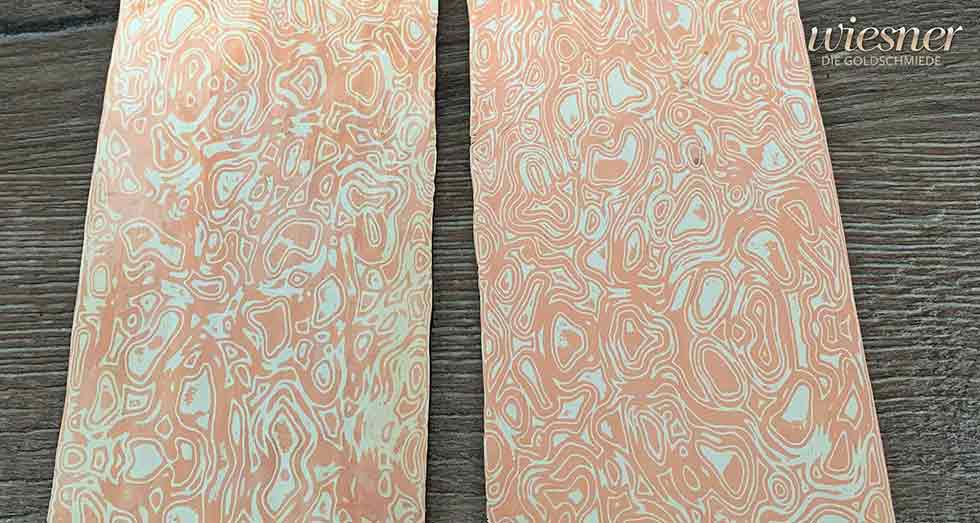

MokumeCover is a thin, usually 0.5 - 0.8 mm thick Mokume Gane sheet, which is wrapped around an existing stainless steel or precious metal wedding ring and soldered to it. It should be noted that the mokume gane sheets used are usually actually welded and patterned precious metals. Here too, yellow gold, white gold, red gold, green gold, platinum or palladium, as well as silver, may have been used. The combination of copper and silver is also frequently found in mokume covers.

Like GravoMokume, MokumeCover can be recognized first by the fact that the typical pattern on the inside and edges of the wedding rings is not to be found. Another distinguishing feature is the pattern interruption, which is usually present and can be clearly recognized as a transverse line on the outside of the rings. In very rare cases, an endless pattern can also be found.

Compared to GravoMokume, MokumeCover wedding rings are somewhat more complex to produce. It is virtually impossible to change the ring width of MokumeCover wedding rings, especially to extend them.

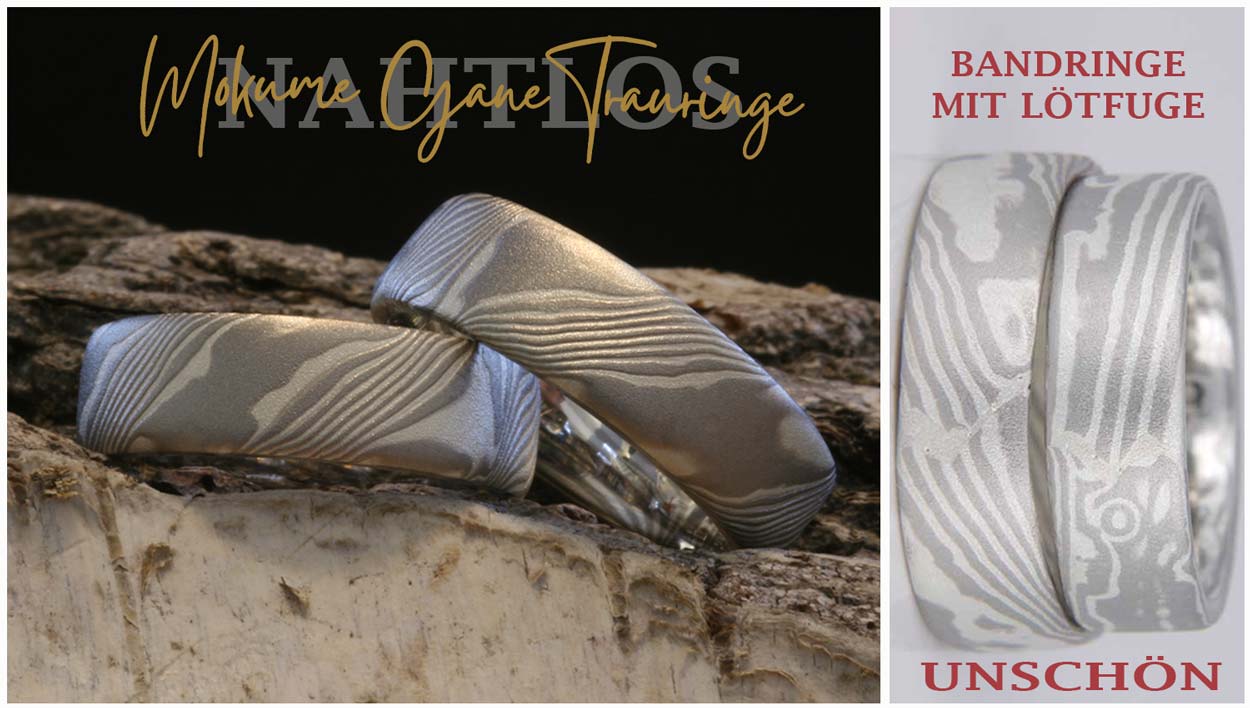

Mokume Seam (soldered band ring) compared to Seamless:

MokumeSeam wedding rings are also known as band rings because of the way they are made in the goldsmith's trade. A mokume gane strand is made from various precious metals, or possibly also non-precious metals, and rolled into a sufficiently long band.

The goldsmith then forges this band into a round ring until the two ends of the band touch. The wedding ring is then soldered there.

This is a tried and tested technique used by goldsmiths to make rings or wedding rings. In this respect, this technique is of course also used in the manufacture of many a mokume gane wedding ring.

Occasionally, we have also been able to find MokumeSeam wedding rings on the web, which have been very skillfully soldered together diagonally in a diagonal pattern. Even an expert has to look closely to recognize this time-saving trick. MokumeSeam wedding rings can cause serious problems when the ring width changes and can break open at the solder joint.

Mokume Seamless

Mokume Gane wedding rings in seamless technique (traditional technique, forged endlessly without a seam)

This is the traditional forging technique for mokume gane wedding rings, as produced by any goldsmith who accepts and masters the challenge of splicing mokume gane material.

Basically, this is the only design that does justice to the symbolism of a wedding ring, namely endlessness. These traditionally made mokume gane wedding rings can be recognized by the pattern that is visible on the inside and outside and runs around the ring without interruption. In addition to the advantage of having no unsightly pattern interruptions, the ring width of endlessly crafted mokume gane wedding rings can easily be changed.

"Wiesner - Die Goldschmiede" exclusively offers Mokume Gane in seamless technique (traditional technique, endless pattern).

Some insights into our Mokume Gane wedding ring workshop Meta: Videos about the Mokume Gane production of wedding rings / Mokume Gane wedding ring production videos from the goldsmith's workshop to illustrate the working methods of master goldsmith Markus Wiesner.

Videos from our goldsmith's workshop:

Production of seamless Mokume Gane wedding rings

1) Mokume Gane wedding rings | The ingot:

Master goldsmith: Markus Wiesner | Music: Michael Wiesner

2) Annealing, rolling, annealing, rolling | How Mokume Gane wedding rings are made

3) Mokume Gane wedding rings | The pattern is applied

4) And forging and rolling again.

5) Marking and drilling the mokume gane rings

What are mokume gane rings?

A special centuries-old Japanese art of forging

The mokume gane technique originated in Japan around 350 years ago. Mokume Gane wedding rings, which are made using this ancient Japanese forging technique, are very special and unique. Mokume Gane wedding rings are created by welding together thin layers of precious metal, which are then forged and patterned. In this way, new and unique patterns and color gradients are created again and again - depending on the precious metals and patterning techniques used. A pair of mokume gane rings is always made from a single piece of welded base material. This makes the two Mokume Gane wedding rings very similar.

Hand-forged in countless different designs

Just as individual as the patterns of the mokume gane rings are, your wedding ring can be made just as individually for you. The ladies' ring, for example, can be embellished with a single diamond or with many small stones.

Mokume Gane wedding rings made from precious metals

Whether gold, silver, platinum or palladium - we forge mokume gane rings for you in a wide variety of materials. We will be happy to make a completely individual pair for you.

Wearing comfort of Mokume Gane partner rings

Of course, in addition to their appearance, the wearing comfort of partner rings, including mokume gane wedding rings, also plays a major role. After all, the wedding ring accompanies you day after day. For this reason, the ring height, width and profile are adapted to your personal preference.

Any questions about mokume gane wedding rings? We are happy to help you at any time.

Whether in person in our store or over the phone - we will be happy to help you choose the perfect Mokume Gane wedding rings and advise you in detail. Let us inspire you and find the right wedding rings for your big day and your whole life in our studio. Is it also possible to have a single ring or engagement ring made? In addition to the Wiesner Mokume Gane ring collection, we also manufacture a jewelry collection and engagement rings using the Mokume Gane technique. We can also make completely custom jewelry rings.

Historical development of Mokume Gane

History of mokume gane: a fascinating craft

Origins of layered steel

The search for better materials for weapon blades ushered in the era of patterned metals. Europeans first discovered sabre weapons made of high-quality steel in Damascus and mistakenly referred to this material as Damascus steel. This steel impressed with its strength and power, as well as its wavy flame pattern. Although it appears that the development of this new steel took place independently in different regions of Europe and Asia, there are references to it in Norse sagas and archaeological excavations from Roman times.

In China, layered steel appeared in the 1st century BC, Japanese samurai and their weapons masters developed the technique further and welded the steel to be high-carbon. A well-known Japanese swordsmith named Shoami (1651-1728) from Akita made a name for himself as the first person to weld non-ferrous metals with steel and precious metals and form them into artistic decorations. He called it mokume gane.

Mokume Gane in Japan

The mokume gane technique became established in Japan due to advanced sword-making techniques, extensive knowledge of metallurgy and an excellent exchange of information in large schools. In addition, Japan had unique colored metal alloys such as red copper (shibuishi and kuromido), which were created due to the scarcity of precious metals such as gold and silver, but were still rare and expensive.

Why was mokume gane unknown for a long time?

For a long time, the technique of mokume gane was not known abroad, as Japan was a remote island until 1853 and the techniques of Japanese artists and craftsmen were kept secret. The fact that mokume gane is a very demanding technique that requires a lot of practice and skill also contributed to the fact that it remained a well-kept secret for a long time

Europe's industrial revolution prevents its spread

Secondly, the industrial revolution developed in Western countries, causing seemingly alchemical craftsmanship and sentiment to become increasingly unpopular.

Turning point of Mokume Gane

It was not until the 1960s that jewelry changed from a purely decorative and prestigious investment to an increasingly artistic approach. The discovery of mokume gane in the United States in the 1970s laid the foundation for further development. It was Hiroko Sato and Gene Pijanowski who began working with mokume gane in the 1970s. After some unsatisfactory results, the two traveled to Japan to learn the classical technique of mokume gane. On their return to Japan, they continued to develop mokume gane techniques, in particular the production of large vessels and jewelry.

- 1970: Brazing of metal layers by George Sayer, USA

- 1978: Mc Cullum from England travels to Japan to learn the art of Mokume Gane and returns to England to produce wonderful pottery.

- 1980: Stefan D. Kretschmer in the United States learned the mokume gane technique from Sato and Pijanoski and has been working on gold mokume gane ingots without the use of solder ever since.

Since mokume gane requires a considerable amount of time and materials, it did not become popular in the early days due to the labor hours and cost.

Mokume Gane wedding rings - costs and production time

How much do mokume gane wedding rings cost?

In our store you will find some examples of pairs of wedding rings with the corresponding prices. However, as Mokume Gane jewelry is unique and is designed individually in consultation with you, we do not usually work with fixed prices. We will of course be happy to prepare an individual quote for you. For this reason, we would like to invite you to a consultation in our studio or, if you are inquiring from a greater distance, we can also offer you a non-binding preliminary consultation by telephone. Simply send us a short email with your telephone number. We will be happy to call you back. You can also contact Mr. Michael Wiesner directly on +49 (0) 7062 22991 for a consultation. To give you a small indication of the prices of Mokume Gane rings : You can calculate from approx. 2,000 euros for well-crafted, endlessly made wedding rings.

How much time do you need to allow for the production?

We generally estimate a period of 4 - 8 weeks for the production of your mokume gane wedding rings. However, we can bring your order forward in individual cases. In this case, your rings can be completed within a week. Please contact us in any case. Simply send us a short email with your telephone number. We will be happy to call you back. You can also contact Mr. Michael Wiesner directly at +49 (0) 7062 22991 for a consultation, or contact us via the contact form at the bottom of the website .

Mokume Gane wedding rings - ring profiles, width and thickness

The ring thickness or profile height of mokume gane wedding rings is freely selectable.

The ring thickness, also known as the profile height, can be customized for Wiesner Mokume Gane wedding rings . We usually use a dimension of 2.0 mm. However, this can be increased or decreased according to your individual wishes. When using diamonds, it is sometimes necessary to increase the height of the ring profile, depending on the height of the stone. Ultimately, however, the decisive factor for the profile height should be your personal feeling when wearing the ring. If the profile is too high, this can be annoying on the neighboring fingers or cause pain when a firm handshake is applied.

Ring profiles for mokume gane rings.

As mokume gane jewelry and wedding rings are made to order, almost every conceivable ring profile is possible. Here are a few examples:

- flat on the outside

- slightly curved on the outside

- medium curved on the outside

- strongly curved on the outside

The curvature of a ring profile is often referred to as cambered or stretched. The insides of our rings are usually slightly domed. This significantly increases wearing comfort. Especially on days when your fingers are slightly swollen, the ring still glides over the finger joint. With wide rings, from approx. 6 mm and wider, this also allows better ventilation of the skin under the ring.

The ring width of Mokume Gane wedding rings

The ring width of MokumeGane wedding rings can be individually adjusted to your wishes. It makes sense not to go below 4 mm with the ring width. Mokume Gane wedding rings are characterized by their beautiful patterns. The narrower a ring is made, the less of the patterns can be seen. There are only upper limits to the ring width in terms of wearability. Here, we consider a ring width of 14 mm to be the size that is still comfortable to wear. However, this is ultimately a subjective feeling and may vary in individual cases.

Allergies with mokume gane wedding rings

Silver is often used for mokume gane wedding rings

During consultations, the question often arises as to why many Wiesner Mokume Gane wedding rings contain layers of silver and whether these can also be replaced with white gold. In principle, of course, white gold can also be used. We use silver if the rings are to be given a 3-dimensional structure on the surface by etching. This involves reducing the height of the silver slightly. This is only possible to a limited extent with white gold and often leads to unsightly results. Furthermore, the silver with its light color forms a beautiful contrast to other precious metals such as palladium, yellow gold or red gold. White gold and palladium, on the other hand, hardly create any attractive color contrast.

Are there any known allergies to mokume gane wedding rings?

Wiesner mokume gane wedding rings are made exclusively from nickel-free precious metal alloys. The now widespread nickel allergy is therefore excluded.

Diamonds in mokume gane wedding rings

Can diamonds be incorporated into mokume gane wedding rings?

Of course, it is alsopossible to incorporate one or more diamonds into Wiesner Mokume Gane wedding rings (brilliant = brilliant-cut diamond). We usually work with the diamond quality fine white, small inclusions (TWSI). However, any other quality can be used on request. Diamonds can always be rubbed into the surface of the ring, i.e. set flush with the surface.

However, it is also possible to set a larger brilliant-cut diamond (from approx. 0.10 carat) as a tensioned stone in a ring shank that is open at the top. In addition to brilliant-cut diamonds, we also work with princess-cut diamonds, navette-cut diamonds, heart-cut diamonds and many other cuts.

Ring changes for mokume gane wedding rings

Is it possible to change the ring on mokume gane wedding rings?

There is a widespread opinion that the width of MokumeGane rings cannot be adjusted. This is not correct. Wiesner Mokume Gane wedding rings can be widened or narrowed by any experienced Mokume Gane goldsmith. This is done using a process that is already used during the manufacture of your wedding rings. Of course, the surface then needs to be reworked, as is the case with many classic wedding rings.

Under no circumstances should you take your Mokume Gane wedding rings to a goldsmith or jeweler who is not familiar with Mokume Gane. There is a risk that they will try to stretch the rings or saw them open to remove or insert parts. If the rings are stretched, they could possibly burst open; if they are sawn open, the beautiful pattern will be partially lost in any case, or the rings will lose the symbolic character of endlessness.

Mokume Gane wedding rings are elaborately produced by us in the traditional way by slitting and splicing in order to preserve this symbolic character. For more detailed questions, simply send us a short email with your telephone number. We will be happy to call you back. You can also contact Mr. Michael Wiesner directly at +49 (0) 7062 22991 for a consultation.

Suitability of Mokume Gane wedding rings for everyday wear

Mokume Gane wedding rings are suitable for everyday wear

Mokume Gane wedding rings are in no way inferior to traditional wedding rings in terms of the durability of metal colors and surface structures. Signs of wear are completely normal for both conventional wedding rings and mokume gane wedding rings and occur to a greater or lesser extent depending on how they are worn. You can return your Wiesner Mokume Gane wedding rings to our goldsmith's workshop once a year free of charge (excluding postage) for reconditioning.

Tarnishing of Mokume Gane wedding rings

Color changes due to the well-known tarnishing of precious metals only occur in very rare cases. The cases we have become aware of so far have been caused by water additives in swimming pools, such as chlorine or silver ions (the latter is often used in pools in the USA). It is advisable to remove the wedding rings before entering the swimming pool.

Mokume Gane wedding rings and abrasion of the surface

The popular structure of the Wiesner Mokume Gane wedding rings can change minimally over the years and decades due to abrasion (1/100 millimeter range). However, the long duration of this process makes it almost impossible to consciously perceive. As the wood-like structure of Wiesner Mokume Gane wedding rings moves through the entire ring cross-section, it is impossible for the pattern to disappear.

Mokume Gane and wedding rings

Mokume gane is a centuries-old forging technique from Japan.

It developed from the art of forging swords. The far better known technique of Damascus steel forging, which in our culture takes its name from the first place where it was found, Damascus in Syria, gave rise to the welding and structuring of the mokume gane.

Decorative elements on the hilt and grip, as well as the scabbard, were first made by Denbai Shoami from softer alloys with a high copper content. As the precious metal gold was very rare to find in Japan and therefore very expensive, the gold content of the mokume gane alloys of the time was limited to around 4%. The remaining content was primarily copper and silver.

Even today, mokume gane goldsmiths still frequently work with alloys such as Shibuichi, or Shakudo. After sampling the layered and welded sheets, wonderful colors can be achieved with these alloys by creating a patina using various stains.

However, as these are purely superficial, they can rub off very easily when wearing wedding rings, for example. For this reason, all these beautiful colors cannot be used in the production of MokumeGane wedding rings . Here, time-honored precious metals such as gold, silver, platinum and palladium have proven their worth. Of course, white gold alloys can also be used, but this is rarely used due to the lower contrast to the other metals and the higher price compared to palladium.

We always weld the mokume gane base material for the wedding rings from our workshop ourselves in a temperature-controlled welding process in the furnace. Depending on the material composition, the layered and clamped precious metal layers remain in the furnace for between 10 and 15 hours. Without any solder or other bonding agents, a so-called sintering process takes place in which the atoms begin to mix at the boundaries to the respective neighboring sheet. This happens in the 1/1000 millimeter range. Every small impurity or fingerprint between the sheets disrupts this sintering process and renders the mokume gane ingot unusable. This can then only be broken down again chemically in a refinery.

Once the welding is successful and the ingot has cooled down again, the actual production of the mokume gane wedding rings begins. First, the mokume gane ingot is forged and rolled to the appropriate length and cross-section. At regular intervals, the material must be relaxed by annealing. During this so-called recrystallization annealing, the partially broken atomic structures realign themselves. The precious metal regains its pliable properties and can be shaped further. Once annealed too late, the material visibly tears or welds come loose, making the mokume gane ingot unusable.

Once the material is the right length, the splicing process begins. Slits are cut into the strand, which are then expanded into round rings using small chisels and later a steel mandrel. This is the only method with which mokume gane wedding rings can be produced without interrupting the pattern and without unsightly seams. This seamless technique is not used by all mokume makers, as it is very time-consuming and requires a great deal of skill and practice.

However, the result is all the more beautiful. The symbolic power of endlessness.

More Mokume Gane jewelry and collections:

Mokume Silver" collection

A Mokume Gane jewelry collection by Michael Wiesner

The "Mokume Silver" collection was designed by Michael Wiesner, one of the two owners of "Wiesner - Die Goldschmiede", with the aim of offering a small but fine line of Mokume Gane jewelry that combines both the uniqueness of this wonderful craftsmanship and the cost advantages of small series production. The aim was to create unique pieces that are priced well below the usual one-off production of mokume gane in order to open up this wonderful forging technique and its visual appeal to a wider circle of enthusiasts.

Mokume Gane jewelry and CAD design

For the reasons mentioned above, Michael Wiesner has designed the four basic models Funa, Kora, Gongu and Kokoro using CAD design and has thus already prepared the basic bodies of these pieces of jewelry for casting. Today, the basic bodies of the Mokume Gane Silver collection can be cast in silver from molds made directly from the CAD drawings. Steel molds could also be milled as negative molds in which Markus Wiesner can forge the artfully prepared Mokume Gane elements into shape. These then fit exactly onto the previously cast base bodies of the pieces of jewelry. The mokume gane elements are then soldered on and the transitions to the plain silver are trimmed.

Which models are currently available from the "Mokume Silver" collection?

There are basically the following models, each of which is available as a pendant, ring and ear stud:

- Mokume Gane jewelry Funa

- Mokume Gane jewelry Kora

- Mokume Gane jewelry Kokoro

- Mokume Gane jewelry Gongu

Further lines are planned for 2022 and are already being designed.

Mokume Gane semi-finished product as patterned decorative sheet for further processing

Since 2020, we have been offering Mokume Gane semi-finished products, which we design and manufacture individually for craftsmen and manufacturers with a wide variety of products. Particularly high-quality lifestyle products and accessories can be wonderfully enhanced with Mokume Gane elements or given a special look.